From the first beach bars to iconic cultural venues, the city’s buildings trace its transformation - and Bond University is part of the story.

For much of its history the Gold Coast has been a holiday playground, a place defined by sun, surf and escape. But with a population closing in on one million, it has developed a community and culture that extends beyond transient visitors. That evolution is reflected in the city’s architecture which has shifted from tourism-focused designs to buildings that serve residents, culture and civic life, while maintaining the city’s sense of openness and fun.

The original Surfers Paradise Hotel, built by Jim Cavill in 1925 in the village then known as Elston, anchored the centre of what would become known as the Gold Coast. Its large, rambling timber structure with hipped and gabled roofs housed a beer garden and menagerie complete with monkeys.

Pictures: Gold Coast Libraries.

When destroyed by fire in 1936 it was quickly replaced by a masonry and tile structure designed by E P Trewern in a Mediterranean style.

Surfers Paradise quickly became a magnet for holidaymakers, drawing visitors with its eclectic vibrancy and cheeky playfulness even as tourist development spread along the highway south to Coolangatta and north to Paradise Point.

By the 1950s, private holiday homes, serviced apartments and colourful motels with eccentric names like Pink Poodle...

Picture: Gold Coast Libraries.

...and El Dorado were adopting a style now known as Gold Coast Modernism.

Picture: John Gollings / Gold Coast Libraries.

Initially influenced by the architecture of the US Sun Belt states, modernism with its connotations of relaxed, modern living, soon became the Gold Coast’s default architectural expression; a suitable foil to conservative Brisbane.

Chevron Hotel. Picture: Gold Coast Libraries.

Chevron Hotel. Picture: Gold Coast Libraries.

The Chevron Hotel, designed by architect David Bell and constructed between 1958–60, boasted the Skyline Lounge, a beer garden-style bar under a pleated canopy roof.

Skyline Lounge. Picture: Gold Coast Libraries.

Skyline Lounge. Picture: Gold Coast Libraries.

Perched at podium level above the Gold Coast Highway, this very popular venue hosted local and international cabaret acts.

Open-air arcades such as Walk Arcade invited wandering, while motel courtyards like the Beachcomber’s offered glimpses of hibiscus gardens and guests lounging by pools. Neon signage proliferated.

Picture: Gold Coast Libraries.

Holidaymakers accepted the lower privacy settings and loosening of dress codes as part of the informality of Surfers. Here was a shared vision about how buildings contributed to the Gold Coast experience and this experience was made available to everyone by simply being in the public realm.

South of Surfers, Lennon’s Broadbeach Hotel (1957), a landmark building set in tropical gardens, established the centre for another hub of activity at Kurrawa. Designed by Austrian émigré Karl Langer, ‘the Broadie’ provided the Gold Coast with a direct link to the European Modern Movement.

Pictures: Gold Coast Libraries.

It oozed reserved sophistication, yet it too welcomed beachgoers directly into its open-air beer garden.

The 1980s boom

The resort developments of the 1980s were built for a different world. The Sheraton Marina Mirage, designed by Desmond Brooks for disgraced entrepreneur Christopher Skase, featured sweeping lagoons, white façades and luxury retail. It made a decisive play for the high-end market but was disconnected from the city’s public life in a way earlier hotels were not.

Sheraton Marina Mirage. Picture: Gold Coast Libraries.

Sheraton Marina Mirage. Picture: Gold Coast Libraries.

Sanctuary Cove, opened in 1988, embodied the same boom-era ambition. Australia’s first fully integrated resort and residential development combined luxury homes, a marina, golf courses and retail. But as a gated community, it was another turn away from the open, communal character of earlier Gold Coast architecture.

A return to shared spaces

Cities don’t thrive on exclusivity alone. Over time, the Gold Coast rediscovered the value of spaces that welcomed everyone, not just paying guests.

Foremost among them is HOTA, designed by ARM Architecture. It emerged from an existing cultural complex in expansive parklands and was extended to include a purpose-built gallery and outdoor stage. ARM’s masterplan carefully integrates building and landscape to support a vast range of activities, from bike and pedestrian links to Chevron Island to vantage points for taking in the Surfers skyline.

The HOTA gallery itself pairs world-class art with a climb to a perched deck offering sweeping views north to Minjerribah and South Stradbroke Island. HOTA has become a much-loved public venue that brings people together in a civic space that is colourful, relaxed, irreverent and that celebrates the Gold Coast. It is of its place and time.

Bond University

Though a private institution, Bond University was designed as an urban precinct that welcomes the public onto its campus.

The original buildings by Daryl Jackson, alongside the Arch Building by renowned Japanese architect Arata Isozaki, create a striking campus that commands attention.

Pictures: Cavan Flynn.

That spirit of openness made Bond a fitting host for the launch event of Gold Coast Open House 2025, when the spotlight fell on the university’s Abedian School of Architecture.

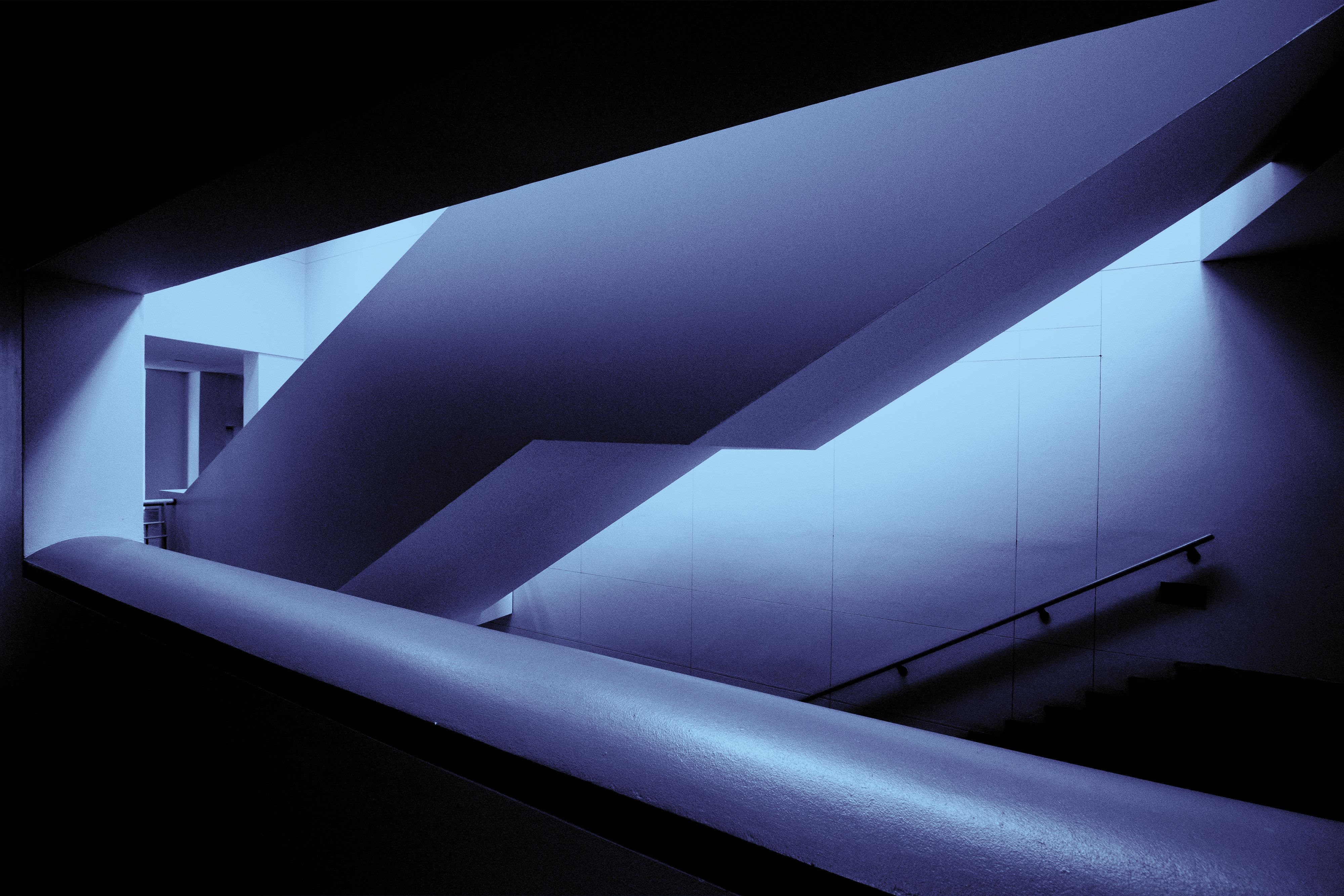

Designed by Sir Peter Cook and Gavin Robotham of CRAB Studios in London, the building was created for studio teaching, but its soaring, light-filled spaces now host music recitals, lectures and community events. It has become a space cherished by students, staff and the wider public – a reminder that architecture is at its best when it brings people together.

In pictures: Gold Coast Open House 2025 launch at the Abedian School of Architecture

Vice Chancellor and President Professor Tim Brailsford, Commander Nicholas Robinson and Governor Jeannette Young.

Vice Chancellor and President Professor Tim Brailsford, Commander Nicholas Robinson and Governor Jeannette Young.

Senlina Mayer, Governor Jeannette Young, Professor Paul Loh and Assistant Professor Mark Bagguley.

Senlina Mayer, Governor Jeannette Young, Professor Paul Loh and Assistant Professor Mark Bagguley.

Senlina Mayer, Governor Jeannette Young and Professor Paul Loh.

Senlina Mayer, Governor Jeannette Young and Professor Paul Loh.

Patron of the Abedian School of Architecture Soheil Abedian and Mayor Tom Tate.

Patron of the Abedian School of Architecture Soheil Abedian and Mayor Tom Tate.

Margaret Blades and Katherine Hopkins from the Gold Coast Chamber Orchestra.

Margaret Blades and Katherine Hopkins from the Gold Coast Chamber Orchestra.

Published Wednesday, 19 November, 2025.

Original thinking direct to your inbox

Stories from Bond