Eyes on the prize

Professor Helen O’Neill closes another chapter of a distinguished research career

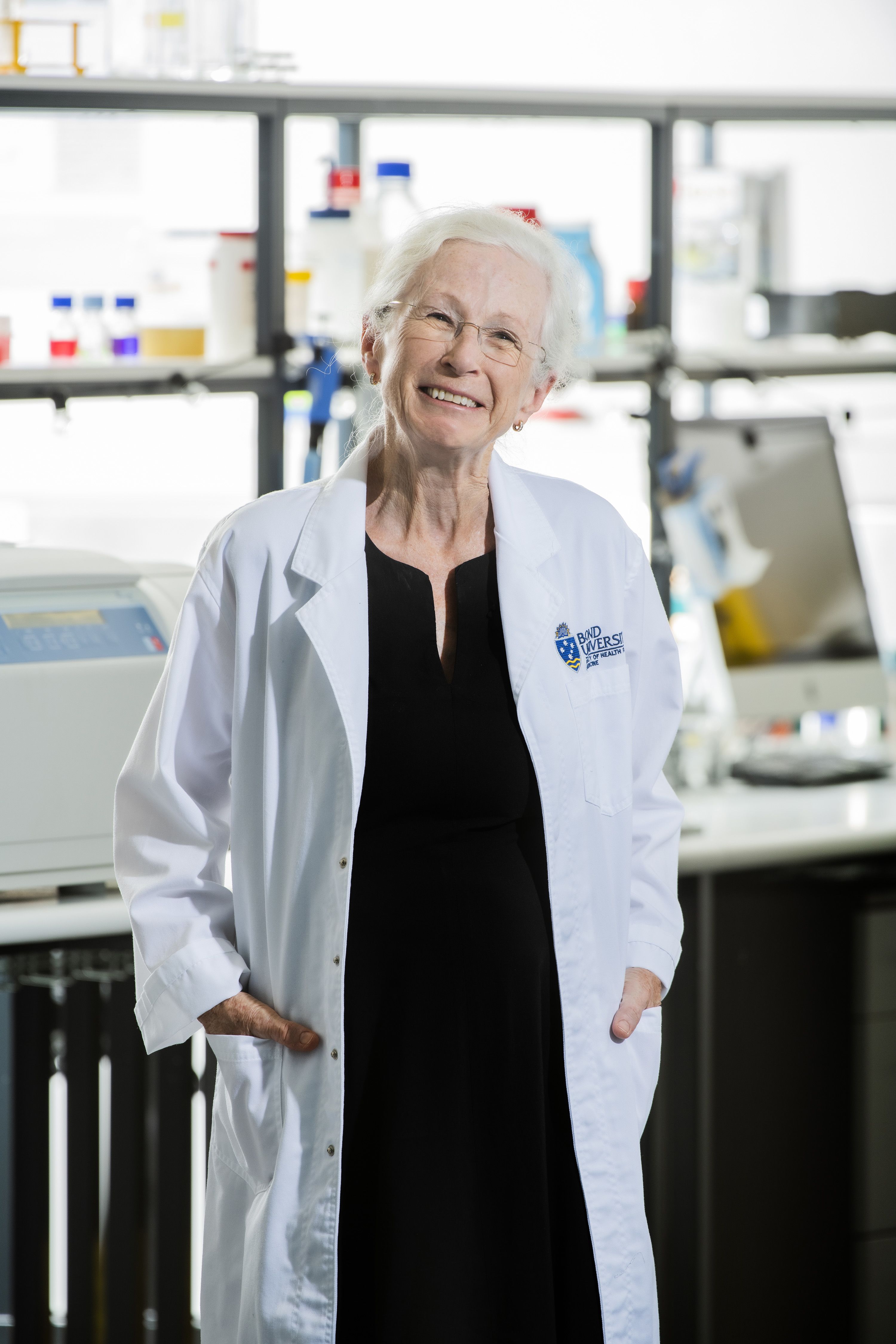

Professor Helen O’Neill is many things — a brilliant and determined mind, mentor, and mother. As she retires from a five-decade-long career at the forefront of one of the most promising fields of science, she shares her path into immunology and stem cell biology, the advances she’s made, and what’s ahead for Bond’s world-leading research into age-related macular degeneration.

Helen O’Neill vividly remembers the moment she boldly declared she was going to university. The backdrop was Adelaide in the early 1960s — a time when few went on to higher education and, fewer still, young women. At just 10 years old, surrounded by friends walking home from basketball, she revealed her dream. The reaction was, perhaps, typical of that era.

“The discussion came up and I said I would go to university. I still remember the blank look on my friends’ faces,” she recalls. “I took a big diagonal across the road, around the corner, feeling alone with my expectation. Fortunately, times have changed.” The world is better for her determination.

Today Professor O’Neill is an internationally leading and highly distinguished academic, who has worked at some of the most prestigious universities in Australia and the United States. She’s been instrumental in the growth of Bond University’s Clem Jones Centre for Regenerative Medicine, which she’s led as Director since 2016. She’s published an incredible 194 papers and 2,620 citations, overseen 34 higher degree research supervisions and attracted more than $9.4 million in grant funding.

Building the foundations

Professor O’Neill credits her parents for her work ethic and early focus on education. “One of the most important things I learned from them was to be responsible, to be independent, to work hard — and to keep working,” she says. “My father taught me to drive when I was 12, so I never had girl hang-ups coming from my family.”

She excelled at school. Her father, an engineer, and mother, who worked full time while raising four children, encouraged her to pursue higher education — a path they never had the opportunity to follow. “In a time of war, they joined the workforce early, otherwise they might have had a different life,” she says.

A talent recognised

Awarded a scholarship to Adelaide University, she was unsure what field of medical science to pursue. “University was difficult for me at first, I found it crowded and impersonal,” she says.

“But as I moved through, I developed an interest in genetics and later immunology. I learned about major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigens, which are central to the immune system, and became a focus of my early research.

“I shared my university experience with my now husband and life partner, Terry. He’s also an academic — a mathematician and statistician.”

Graduating with an Honours degree in genetics, she landed a job at the renowned Stanford University Medical Centre in California. Three years working in a lab and attending lectures further sparked her interest in immunology research. Returning to Australia with significant insight into how research worked through publishing and pursuing grants, she began a PhD in immunology at Australian National University (ANU)’s John Curtin School of Medical Research.

Here she made her first breakthrough, revealing the quantitative dependency of T cell antigen recognition for the MHC antigen – or, in lay terms, the amount of MHC antigen on a cell that determines if it is recognised by a T-lymphocyte to initiate an immune response.

Her PhD was very successful, resulting in 13 papers and garnering another award — a CJ Martin Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). This took her back to Stanford University for further overseas experience. "It was a really prestigious fellowship. There were only one or two awarded in Australia at the time. It was a career high point for me, and an early one," she says.

With husband, Terry, and their two young sons, the family moved back to California, where she worked in Irv Weissman’s lab. A pioneer in stem cell biology, Weissman is described as the ‘father of hematopoiesis’, with his recent work laying the foundation for modern cancer treatments. “Irv was a phenomenal mentor and referee to everyone who came through his lab. I learned so much from that experience,” she says.

At Stanford, she made further discoveries about T cell recognition of retroviral antigens in cancer cells, important knowledge in the development of treatments to eliminate them. Returning to ANU’s John Curtin School of Medical Research, and later the Research School of Biology, she was successful with grant funding and built a team pioneering a rare unknown cell type, the dendritic cell. As the ‘antigen presenting cell’ in the body, it triggers the immune response to eliminate foreign pathogens. The lab developed novel ways to grow these cells from stem cells in tissue culture.

Challenges along the way

While internationally recognised for her discoveries, Professor O’Neill says her early career was not without challenges.

“In the early days, it was a very difficult environment. But I persevered. Only when I was promoted to a Professor, was I able to embrace the independence and feeling that I had licence to just get on with my work,” she says. “Since coming to Bond, I've always felt supported. The inclusiveness has been fantastic and pervades the whole university.”

A new chapter

The exciting opportunity to lead the Clem Jones Centre for Regenerative Medicine lured Professor O’Neill to Bond University. Alongside Terry, who launched the University’s actuarial program and is now Bond Business School Executive Dean, she relocated to the Gold Coast — a place the pair spent many years visiting as holidaymakers.

“It opened a new area for me in stem cell work, which is really exciting. Plus, I live in an apartment overlooking the beach,” she says. “I took great interest in the project, generating retinal cells from pluripotent stem cells, with a translational program to transfer them to the eye of animals — and eventually humans — to restore vision in people with macular degeneration.

“It was an opportunity to do something different, something translational, to end my career.”

The Centre has made significant advances, with the next phase involving commercialisation of its leading-edge technology. “It’s providing hope,” says Professor O’Neill. “Scientists are moving closer to finding ways to transplant cells that can function, and potentially restore vision.

“There are lots of scientific elements that need to be resolved or fine-tuned, but it is starting to happen around the world. People are attempting transplantations, but the system for developing cells at Bond is quite unique and probably superior.”

Professor O’Neill has also continued researching the spleen as an alternative site for hematopoiesis beyond bone marrow. Taking advantage of the spleen’s unique regenerative capacity, her team has developed procedures for stem cell isolation, which leads to cell differentiation and, ultimately, tissue regeneration. Under her guidance, the Clem Jones Centre for Regenerative Medicine has grown significantly, securing 10 research grants worth $6.8 million and boasting a team of up to 13, with several higher degree research students.

Professor O’Neill, inspired by her own experiences, is legendary for her skills in people development, which is credited as a key driver in the Centre’s success.

“Mentorship in research is so important because it’s not a straightforward career. There's no standard career path like becoming an accountant. It's quite unique,” she says. “The work outcomes are always unknown; we do experiments to test our ideas and to find solutions to problems. Only some lead to discoveries. “I proudly keep in contact with all my past students. They have all developed successful careers.”

“Scientists are moving closer to finding ways to transplant cells that can function, and potentially restore vision.”

What’s next?

Professor O’Neill says she’s looking forward to spending more time with her two sons, Michael and Connell, who live in Sydney and Hong Kong. “My sons could not believe I was retiring, because I’ve always worked for their whole lives. They still haven’t accepted it,” she laughs. “Our life together has been very close because we were isolated from family in Canberra and California. As a researcher, I always planned my work around my sons. They learnt early on how to embrace a working life.

“I’m retiring to spend more time with family and for physical activity. Keeping fit is very important to me. I see myself in three places, the Gold Coast, Sydney and Hong Kong.”

Her advice to those starting out? Persistence and perseverance. “You have to be determined. You have to jump hurdles and keep jumping them, and there are lots of them,” she says.

“Success doesn’t happen immediately. But, if you’re a creative person who likes research, you should feed your interest, because it is a fantastic career.”

“Success doesn’t happen immediately. But, if you’re a creative person who likes research, you should feed your interest, because it is a fantastic career.”

Original thinking direct to your inbox

Stories from Bond