The quest to cure blindness

Researchers break new ground on work that could impact the lives of 1.5 million Australians

In a world of light and colour, Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) casts shadows on millions of lives. Research by Bond University offers a beacon of hope.

Navigating the ninth decade of her life, Margaret has been blessed with physical vitality but robbed of the one thing she needs to fully enjoy it — her eyesight.

“It impacts almost everything because your sight is everything,” the Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) patient said.

“If I'm walking through a shopping centre, I know nobody — their faces are blank. Even though I'm 82, I am very fit, so if they could find something to help the (AMD) research, that would be absolutely wonderful."

AMD patient Margaret

AMD patient Margaret

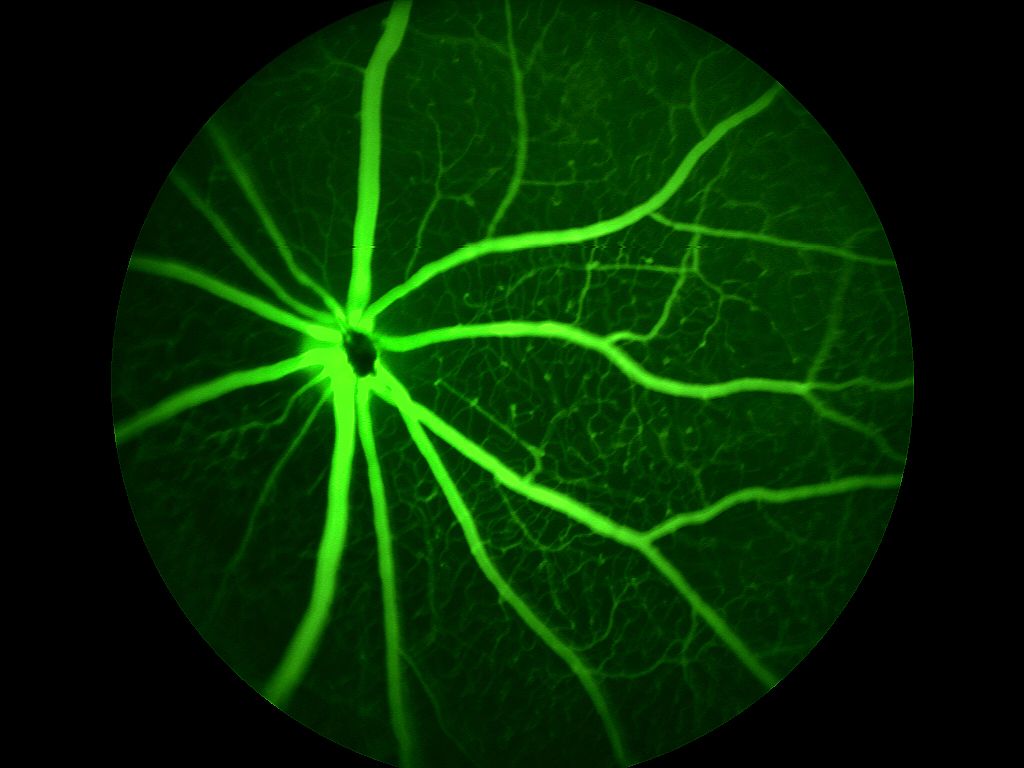

Chances are you or someone you love will be affected by AMD. It's a chronic disease of the macula, the region at the centre of the retina that controls the eye’s ability to focus. The ability to read, watch TV, and recognise faces are all impacted by AMD, which can have a devastating impact on the quality of life and, in many cases, the mental health of sufferers. It is the most common macular disease in Australia, responsible for half of all blindness and severe vision loss. About one in seven people over the age of 50 years suffer from AMD to some extent. That is 1.5 million Australians who would benefit greatly from a viable treatment for AMD.

There are two forms of the disease. Wet AMD is characterised by the formation of blood vessels at the back of the eye. Dry AMD is a combination of the breakdown of the Bruch’s membrane, which maintains the function of photoreceptors and the death of retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells in the macula. Injections have proven to be an effective treatment for wet AMD, but there is no treatment for early, intermediate or late-stage dry AMD.

Researchers from Bond University believe they are on the cusp of reversing vision loss through stem cell therapy where manufactured epithelial cells are transplanted into the eye, reversing the death of photoreceptors that detect light and transmit visual signals to the brain.

AMD at a glance

Age-Related-Macular Degeneration is the most common macular disease in Australia

1 in 7 people over the age of 50 suffer from AMD

1.5 million Australians would benefit from a viable treatment

Finding a treatment for AMD

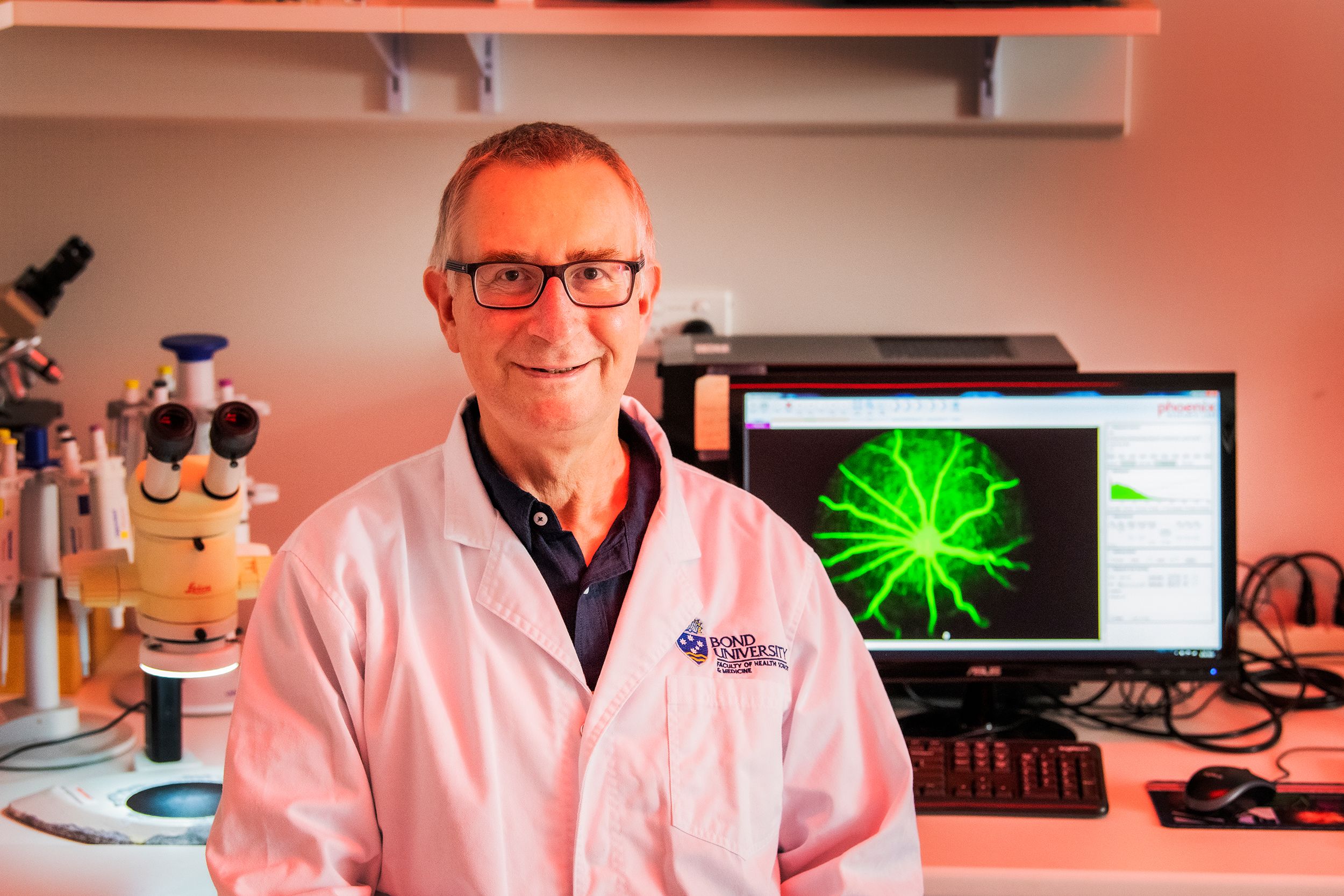

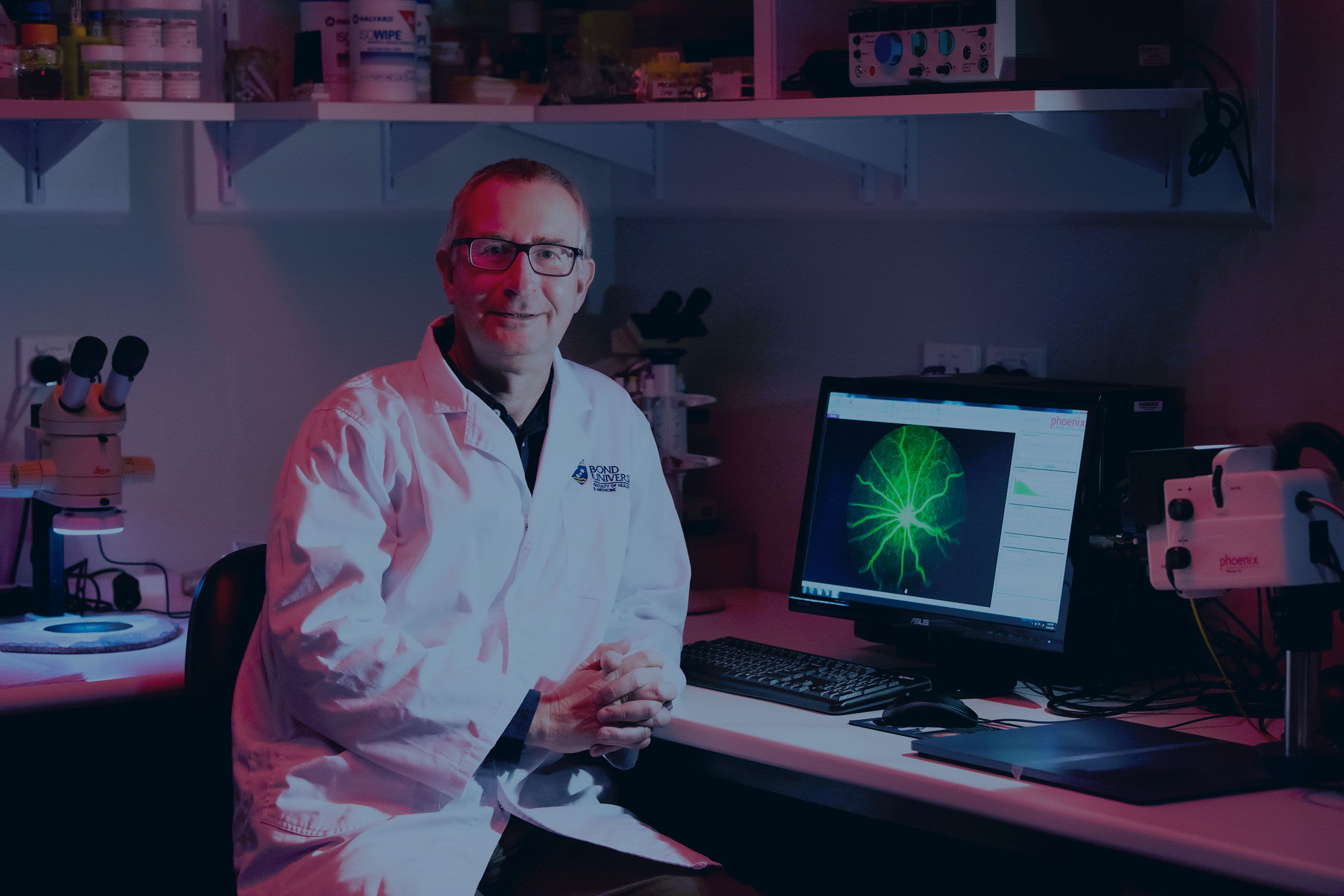

Dr Jason Limnios from Bond University’s Clem Jones Centre for Regenerative Medicine has devoted the past 11 years to seeking a treatment for AMD. He has worked closely with patients like Margaret to better understand the condition.

“They share with me their experience of going blind, their fears of going blind,” he said.

“And they think I understand because I understand the cells, but I don't understand how they feel. All I can see is that their lives are changing and that they're scared - and that motivates me so much."

Dr Jason Limnios

Dr Jason Limnios

"If we can make a whole retina, there’s really no retinal disease that we can't do something about."

Associate Professor Nigel Barnett is an experienced vision scientist who leads the CJCRM’s team of scientists and students, headlined by Dr Limnios. The eminent immunologist Professor Helen O’Neill led the Centre with distinction for more than eight years. Under Helen’s leadership the Centre broadened its activities in regenerative medicine such that it now has expertise in and supports research projects in stem cell differentiation, biomaterials and tissue engineering, and vision science.

The team is working to develop and test a delivery system of stem cell-derived retinal cells, supported by a prosthetic membrane, that can form a uniform layer of retinal cells that function like cells in the healthy eye.

Their work focusses on several areas that need to be developed to generate a stem cell therapy for AMD, A/Professor Barnett said. “The team must perfect the manufacture of cells and the method for implantation to ensure cell survival,” he said.

“We need to increase our understanding of the inflammation that occurs in the eye of AMD sufferers which will impact successful therapy. Drug therapy to allow the body to accept the implant must also be developed.

“We're working on all of these aspects of treatment to make sure that not only do we produce good cells, but that we manage the stressful environment of the diseased eye into which we put the cells.”

Dr Nigel Barnett

Dr Nigel Barnett

Bond's world-leading technology

In 2013, Dr Limnios developed a way to turn stem cells into RPE cells in a process that is compatible with human clinical trials. Speed and efficiency are the major hallmarks of his process, with cells maturing in about 14 days, and 80 per cent of them developing into RPE cells. He has recently developed similar procedures to create rod and cone photoreceptors. These cells are grown on a nanospun polymer membrane that was invented by the first CJCRM Director Patrick Warnke and Qin Liu in 2010.

These membranes can be safely transplanted into a patient’s eye. “Developing the tools has been our strength and we hold patents on several of our procedures, which puts us in a unique position,” A/Professor Barnett said. “One is on the protocol for producing retinal cells from stem cells, which I think is amazing. Jason (Limnios) has generated several protocols for producing cells under clinically relevant conditions. His protocols are fast and efficient and produce cells in numbers suitable for human transplantation.”

Manufacturing RPE cells and Cone Photoreceptors

It was a sliding doors moment that could change the lives of millions of people. Dr Limnios was at Bond University on what was supposed to be a two-month secondment when he discovered a way to mass produce clinical grade retinal cells from stem cells that are safe to transplant into a patient. “I was living in China and I was called over as a favour to help get the project started, and I had a breakthrough pretty quickly,” he said.

“Making retinal cells is challenging, but the way we do it here is different to the rest of the world. Our processes simplify retinal cell production as well as the discovery process itself. What began as a goal to produce RPE cells has grown into a way to make other cell types, that are needed for vision.” Jason says that cone photoreceptors are the key to reversing blindness in late AMD. “In early AMD, RPE cells get sick and eventually start to die off, leaving the cones unable to survive. By replacing the RPE layer we hope to save these cones. However, once cones are lost we need to transplant both the RPE and cones to restore vision. We’ve overcome the barrier to making cones and are working on a combined therapy of RPE and cones for late AMD.”

The next phase

There are two major steps to be taken before the team has a protocol that can be presented to the government regulatory body, the Therapeutic Goods Association (TGA). The cells need to be produced at a scale that allows for efficiency in clinical trials. Dr Limnios is currently working on a design for a robot that would automate the cell development process to remove the variability of human handling.

Surgical techniques for implanting the cells must also be developed through trials on pigs, whose eyes closely resemble human eyes. “The information on safety and efficacy of implants obtained in animals then allows us to consider clinical trials and to approach the TGA for approval,” Dr Limnios said.

The Cutmore Bequest

Cora Cutmore’s was a life lived large. The spirited child of a Darling Downs pioneering family was sent to board at the Church of England Girls' School in Warwick but quickly decided it wasn’t for her and arranged a transfer to Warwick State High School. After graduating she travelled to Brisbane to become a nurse and never looked back.

She became a feared and respected matron, a ward manager who effortlessly matched wits with surgeons she encountered in “her” corridors. The spirit of adventure that led her to leave home at such a young age never abandoned her as her career took her to Melbourne, Hobart and rural communities in Queensland before she travelled to England, Europe, the United States and New Guinea.

In her later years she suffered from AMD. A woman who had travelled the world alone, managed wards in busy hospitals, and amassed a fortune through shrewd share trading, had lost her independence. Realising that her time was nearing an end, Cora entrusted her niece and nephew, Don Cutmore and Janet Price, to find a medical research project that would benefit from her multimillion-dollar share portfolio.

Cora Cutmore died on her 93rd birthday in 2016, but her legacy lives on through the work of the Bond University CJCRM.

“Apart from my two daughters, this is the important thing in my life,” declared Janet Price, whose mother also suffered from AMD. I was charged with a very special project, and that was to find a worthy recipient for my aunt's lifelong frugality. A woman who used the same tea bag three times to save money.

“And this was the project that my cousin and I, two of her most trusted relatives, came up with. And we have had not one regret.”

On the day we visited Janet Price to hear the story of her aunt’s life, she had just returned home from doing the rounds as a volunteer for meals on wheels. The retired school principal met us at the door of her Daisy Hill home determined to make her voice heard. “My aim today is to increase awareness of macular degeneration because no one knows much about it, because it’s not fashionable,” she said.

“If we go blind, they think, well, she's old and she's had a good life. That's kind of the feeling we're all getting, all my age group know someone with AMD. And my friend this morning, we're driving around the different houses for the elderly, and she said, ‘No one cares about us anymore. It's always the young, glamorous sicknesses that are hitting the newspapers. They don't see the old person who now can't read, can't watch TV, who can't find a number on their phone, can't garden, they can't crochet for the grandchildren’. They can’t even babysit because they can't be trusted with the grandchildren in their house. It is that impact on families that makes this cause so important.”

The Clem Jones Foundation

Bond University is proud to have been partnered with The Clem Jones Foundation which supports multiple medical research projects across Queensland. The foundation, a philanthropic organisation established by Brisbane’s longest-serving Lord Mayor, has been a major benefactor to the stem cell research undertaken at Bond University.

CEO Peter Johnstone considered Dr Jones a close friend and mentor and admits he has a personal investment in the work being undertaken at Bond. “Clem Jones had macular degeneration and it was very debilitating for him,” he said. “He was a voracious reader, a studier of media who read books on a daily basis and AMD really stopped all that enjoyment for him. So one of his wishes was to see a cure for macular degeneration.’’

Mr Johnstone said he and the staff and board of the Clem Jones Foundation celebrated the success of the Bond research team and were confident the team were on the path to finding a treatment for blindness. “Clem himself would be down there every day, I'm sure. He'd be inspired by it. He was always inspired by medical researchers in the same way we are.”

Original thinking direct to your inbox

Stories from Bond