Ali Issmail has just graduated from Bond University with a Master of Healthcare Innovations, but his research is already making an impact well beyond the classroom. For his Master’s thesis, Ali investigated a critical gap in Australia’s post-intensive care unit (ICU) care: the absence of structured, timely mental health support for patients after they leave hospital.

For many Australians, surviving an ICU stay is just the beginning of a longer, quieter battle - one that unfolds far from the hospital and often without proper support. While physical rehabilitation is routinely provided, psychological recovery is frequently overlooked.

“ICU survivors are at high risk of PTSD, anxiety and depression,” Ali says, “but there’s no consistent system in place to support them once they’re discharged.

“It’s a silent struggle.”

Mr Issmail’s review found that early follow-up, typically within the first month, can actually retraumatise patients.

“Many patients aren’t psychologically ready to talk about their experience so soon after discharge. It can feel like reliving the trauma.”

Instead, his research suggests that follow-up care should be delayed until patients are emotionally ready - typically after six weeks or more - and should include family members in the process.

“When families are involved, the emotional burden is shared. It becomes a collaborative recovery, not a solitary one.”

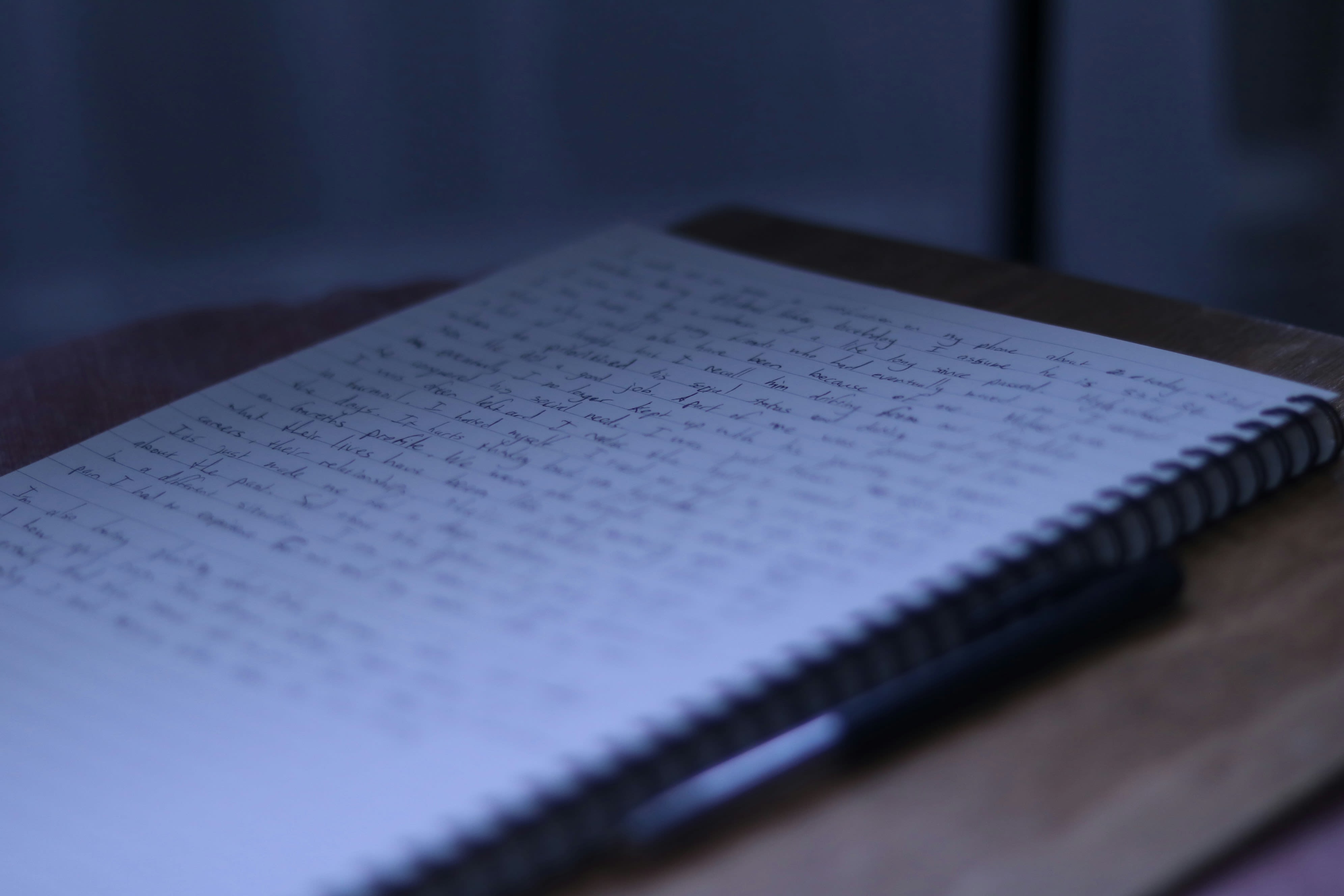

One widely used tool in hospitals is the ICU diary, a journal kept by patients or their families during and after their ICU stay. The idea is to help patients make sense of their experience and track their recovery. But Ali’s research found these diaries can have unintended consequences.

“Once patients are discharged they’re often given the diary to continue updating,” he says.

“But many survivors begin to withhold their thoughts. They don’t want to retraumatise themselves or their families. The diary becomes a reminder of what they’re trying to forget.”

Mr Issmail’s review found that early follow-up, typically within the first month, can actually retraumatise patients.

“Many patients aren’t psychologically ready to talk about their experience so soon after discharge. It can feel like reliving the trauma.”

Instead, his research suggests that follow-up care should be delayed until patients are emotionally ready - typically after six weeks or more - and should include family members in the process.

“When families are involved, the emotional burden is shared. It becomes a collaborative recovery, not a solitary one.”

One widely used tool in hospitals is the ICU diary, a journal kept by patients or their families during and after their ICU stay. The idea is to help patients make sense of their experience and track their recovery. But Ali’s research found these diaries can have unintended consequences.

“Once patients are discharged they’re often given the diary to continue updating,” he says.

“But many survivors begin to withhold their thoughts. They don’t want to retraumatise themselves or their families. The diary becomes a reminder of what they’re trying to forget.”

This highlights a broader issue: while hospitals often provide mental health support during a patient’s stay, those services typically end at discharge.

“There’s a cliff edge,” Ali says. “Once you leave the hospital, that support disappears.

“There are services available post discharge, but we need to make sure patients and their families are aware of them, and that they can access them at the right time.

“The support is out there - we just need to make it accessible, consistent and compassionate.”

One of Ali’s proposed solutions is a national, integrated care model that includes:

Timed follow-up

Delayed psychological follow-up, timed to match patients’ emotional readiness.

Family

Family-inclusive care, recognising the vital role loved ones play in recovery.

Communication

Clear communication about available mental health services, both in hospital and after discharge.

Telehealth access

Telehealth access, especially for rural and elderly patients who may struggle with in-person appointments or digital platforms.

He also calls for the development of standardised mental health indicators, similar to those used for physical recovery.

“We can measure how well someone’s lungs are functioning or how far they can walk. Why can’t we do the same for their mental health?

“The mental health burden can be just as serious, especially for those who’ve survived traumatic events.”

Ali’s findings come at a time when Australia’s healthcare system is under increasing pressure.

His research was undertaken in collaboration with Mental Health First Aid Australia.

The 21-year-old from Sydney, who hopes to become a heart surgeon, said the course gave him the confidence and platform to tackle real-world issues in the health system.

“This degree was transformational,” he says.

“It wasn’t about memorising theory. It was about identifying where healthcare can do better and being empowered to act on it.”

Published on Wednesday, June 18, 2025.

“It wasn’t about memorising theory. It was about identifying where healthcare can do better and being empowered to act on it.”

Published on Wednesday, 18 June, 2025.

Original thinking direct to your inbox

Stories from Bond