Professor of Finance David Gallagher, Associate Professor Chris Bilson and PhD candidate Isaac Tonkin examined investment returns in 16 countries stretching back to 1870. This is what they found.

Property versus shares: it’s the perennial investment debate. Investors have long weighed the benefits and drawbacks of both assets in search of better returns.

In Australia, anecdotally, property is often seen as a ticket to financial security, particularly in retirement. The current poster child for Australian property is Brisbane, where home values have surged 70.6 percent since the pandemic.In comparison, the S&P/ASX 200 rose 82 percent from its Covid-19 era low on March 27, 2020 to 7699 points mark on August 8, 2024. But investing is a long game and both results represent a small snapshot in time.

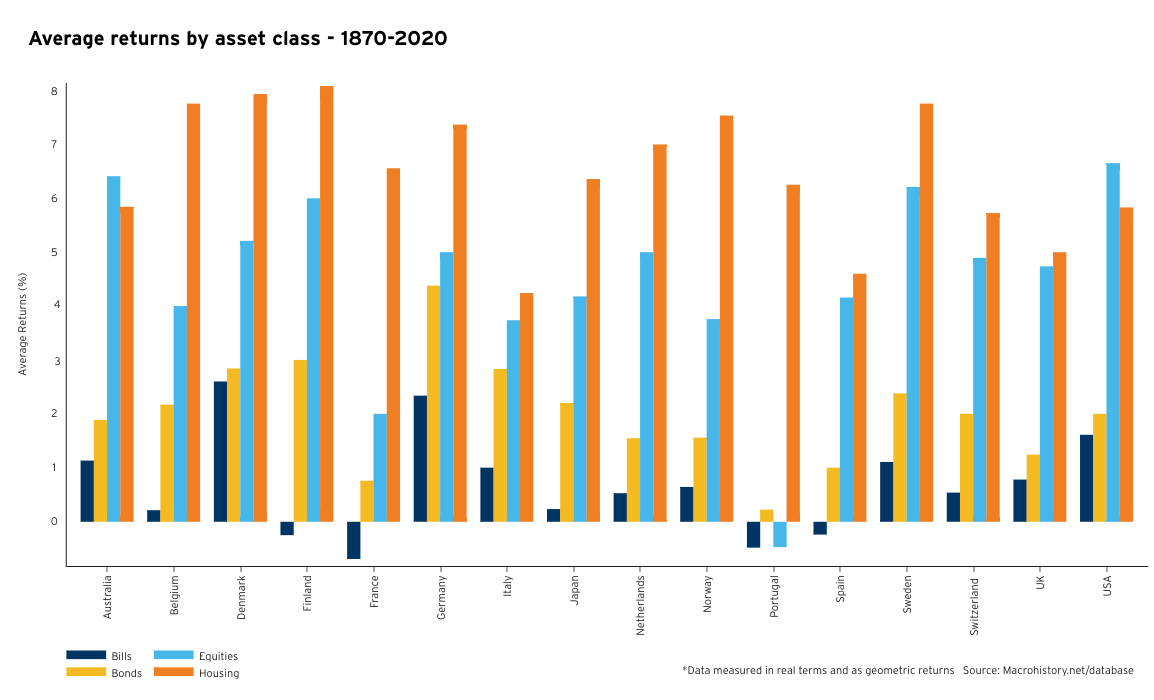

To provide a broader perspective, Bond University Professor of Finance David Gallagher, Associate Professor Chris Bilson and PhD student Isaac Tonkin examined ‘long-run’ investment returns in advanced Western economies since 1870. Among their many findings, Australian shares performed slightly better as a long-term investment.

Their research also confirms a common Millennial lament: the Boomers got it good. Riding a wave of unprecedented economic growth and prosperity, this generation born between 1946 and 1964 has been among the most blessed investors in modern history.

The Boomers' children, primarily members of Generation X (born 1965-1980), may end up doing just as well as they inherit their parents’ US$3.5 trillion wealth and reap the benefits of compulsory superannuation in Australia, introduced early in their working careers.

But the picture is potentially less rosy for all generations following the Boomers as they face higher housing costs, an aging population they will need to support through taxation, significant national debt in the wake of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis and global geopolitical instability.

What countries does the research cover?

The researchers examined 16 advanced Western countries: Australia, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and US. They used data from the Jordà-Schularick-Taylor Macrohistory Database which brings together annual economic data for 16 countries since 1870.

What asset classes were compared?

Property

This includes the family home and any investment properties. It's 'the great Australian dream'.

Shares

Also known as stocks or equities, shares represent units of ownership in a company listed on a stock exchange. Shareholders are part-owners of the company, entitling them to a portion of its profits via dividends, and potentially capital gains.

Bonds

When you buy bonds, you are lending money to a corporation or government in exchange for interest payments plus the return of your initial loan at maturity.

Treasury bills/notes

Shorter-term investments compared to bonds, treasury bills are considered the least risky form of investment because they are backed by an issuing government. Lower risk means a lower rate of return. Financial markets deem them to be ‘risk-free’ instruments.

Why does this study matter?

Many of us will rely on investment returns for retirement income, whether through superannuation, investment properties, shares, or a combination of these. Even though we may not personally invest in shares, bond and bills, our superannuation fund almost certainly does. Examining how different types of investments have performed over the past 150 years gives clues to potential future returns and pitfalls.

What factors influence financial returns?

Inflation

It’s the word on everyone’s lips at the moment from the federal Treasurer down, and it is driving up the cost of living.

“We're all quite aware of the high level of inflation in Australia,” Professor Gallagher says. “Inflation is not a good thing for an economy because it erodes purchasing power – your dollar buys less and less. “As an investor, if your purchasing power is being eroded then you're going to need to be compensated with higher returns. And that is not necessarily something that is guaranteed.”

Technology

Technology turbo-charges investment returns because it enables increases in productivity – that is, technology can get more output from the same input. In the last 150 years, investors have benefited from the mainstreaming of technologies such electricity, the internal combustion engine, electronics, aerospace and the internet. We are currently entering the so-called sixth wave of innovation, which includes artificial intelligence, robotics and the generation of green energy.

“Innovations have a profound impact on the way we live and living standards, but they also have implications for efficiency and productivity,” Professor Gallagher says. “Every wave from the third, fourth and fifth has led to an increased equity risk premium - that is, a premium of return that we get over and above a risk-free asset.”

Demographics

The make-up of a population can have a significant impact on a country’s prosperity. In many Western countries, people are living longer and having fewer children, meaning a shrinking workforce must support growing social welfare and health costs for the elderly. Countries with young populations, such as Indonesia, will probably perform better in the years ahead as they will have an abundant workforce contributing to economic growth over many decades to come.

Geopolitical and sovereign risks

The last 150 years of history is littered with events that rattled markets and investors’ confidence: two world wars, the Gulf War, 9/11 and more recently the Ukraine War. The policy decisions of individual governments can also upend financial stability, such as former UK Prime Minister Liz Truss’s mini-budget of 2022 which tanked the pound and drove up interest rates.

“(In this study) we're looking at things like, can a government service its debt? Will it make its payments on its bonds to its bondholders?,” Professor Gallagher says. “If they can't repay the debt, then that will obviously be a significant challenge to an economy. We also are interested in the freedom of international trade because tariffs or other kinds of embargoes can have an effect on the health of an economy. Looking at a long-run returns, we need to be aware that there are exogenous impacts on markets that we can't avoid.”

What are the lessons?

Australians have historically had an obsession with property and owning their own home – the great Australian dream. But Australian housing and shares have produced similar returns over more than a century, with shares coming out slightly ahead.

In fact, among the 16 countries examined in the study, only Australian and US shares outperformed housing. In many of the other countries covered in the study - particularly the Nordic nations - housing performed much more strongly than in Australia.

The luckiest generation

When you were born can have a profound impact on the performance of your investment portfolio. Professor Gallagher and Mr Tonkin examined how different generations fared across 150 years and found a clear winner.

“Perhaps given the phenomenal advances in technology and population growth, not to forget the enormous productivity gains and economic developments that the Baby Boomers have experienced, demographers might one day re-name that incredible generational cohort ‘the luckiest generation’,” Professor Gallagher said.

“They have experienced phenomenal asset returns over their lifetimes. As they move into retirement, they own a very large fraction of the total wealth of a country. One of the things that's really interesting is that in the next 25 years, about $3.5 trillion of assets in Australia is going to be inherited by their kids. in the meantime, as they transition to retirement, their asset mix is going to change. They're going to be looking to shift their exposure to equity assets and property into less volatile income-producing assets such as bonds and interest-bearing type assets.”

Outlook for later generations

In generational terms, if you’re part of the Millennial through to Generation Y cohorts, that is, Y (born 1980-1994), Z (1995-2009) or Alpha (2010-present), the news isn’t great, Professor Gallagher admits.

"Australia has about $984 billion of accumulated federal debt, America has about $34 trillion and counting," he says. "That is equivalent to about 124 percent of GDP and it's increased in the last 10 years by about 25 percent. That debt will have to be repaid and it's probably going to fall to the younger generations.”

That’s just part of the generational inequality time bomb. Younger generations will be called upon to fund care for aging citizens who are living longer, leading to pressure to lift the pension age beyond 70, and more countries following Australia’s lead on self-funded retirement (superannuation). Those same oldies will be able to stay in their own homes longer, reducing the supply of housing for families.

A toxic soup of higher debt, higher interest rates and low economic growth risks a major recession. And then there’s the unknown implications of AI on unemployment rates and the global headwinds of trade (and actual) wars. As a member of Generation Z, Mr Tonkin, 24, has skin in the game.

"It will be interesting to see how events unfold, particularly with respect to how the nation tackles housing affordability, rising debt levels, and an aging population," he says.

"There's optimism that the productivity improvements brought by new technologies such as AI will help to address some of the issues facing future generations. We're interested in examining these factors - factors that investors and policymakers will need to keep in mind going forward."

Data sources include Òscar Jordà, Katharina Knoll, Dmitry Kuvshinov, Moritz Schularick, and Alan M. Taylor. 2019. “The Rate of Return on Everything, 1870–2015.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(3), 1225-1298.

Original thinking direct to your inbox

Stories from Bond