Bridging law and land

Dominic McGann connects the world’s oldest living culture to some of the nation's biggest projects

This Law alumnus knows a good negotiation means giving everyone a voice – even a cockatoo.

On any given day, you’ll find Dominic McGann wearing one of four hats. Sometimes it will be paired with a suit and tie in the Brisbane offices of law firm McCullough Robertson, other times with RM Williams boots and a hat to beat the heat in the wilds of western and northern Australia.

But no matter his attire, the project he’s working on is probably helping to keep the nation’s economy running. If it’s a major renewables or resources project, there's a good chance Dominic is involved in the negotiations one way or another.

“In most transactions I either act for the government, for the affected Aboriginal or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, for the proponent of a project, or for other landowners who have an interest in it,” he says.

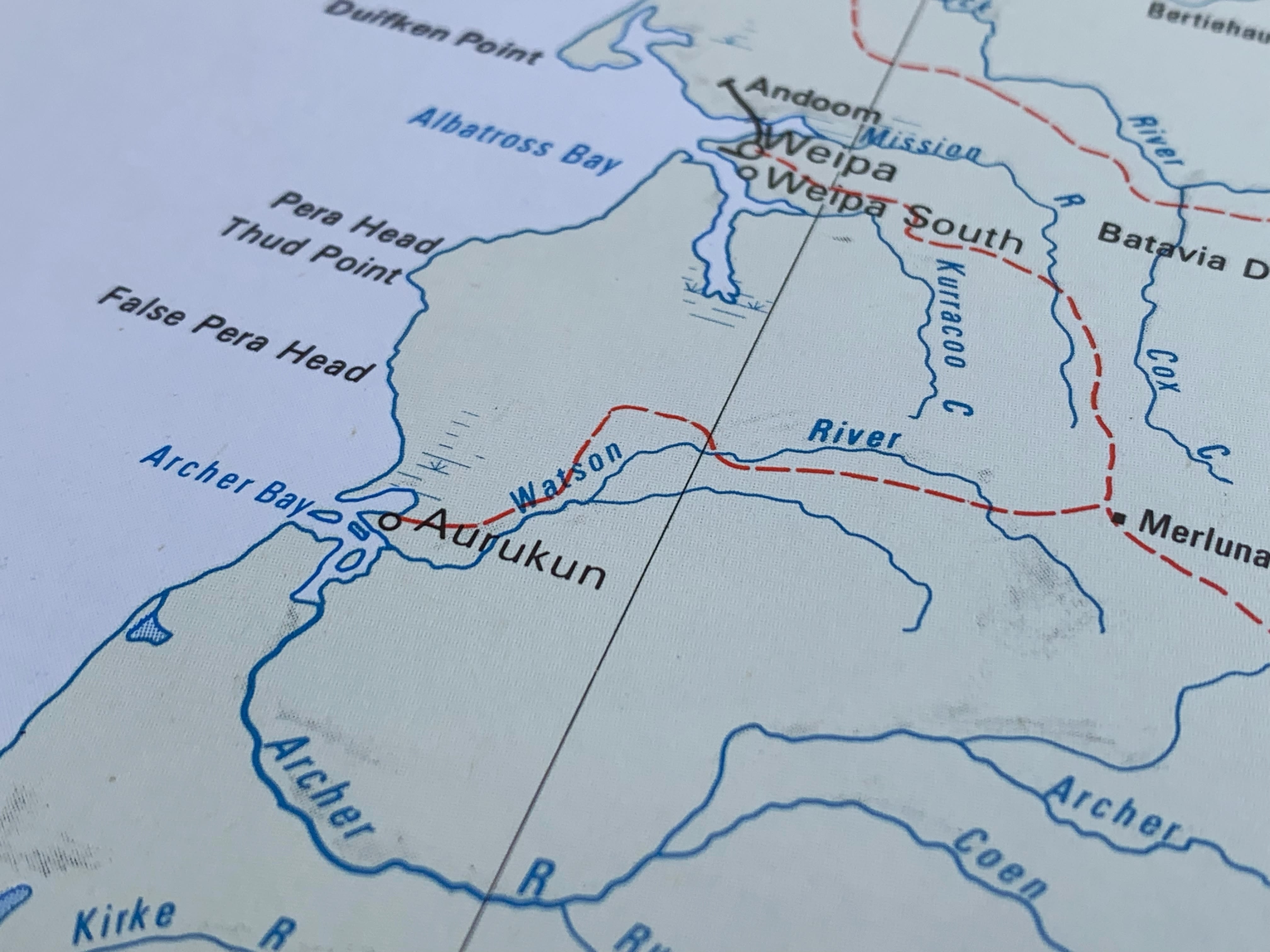

“Our firm does a lot of work for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, particularly the Wik and Wik Waya people of Western Cape York, looking at their engagement in terms of new projects like the Aurukun Bauxite Project or their carbon and conservation arrangements.

“The Wik and Wik Waya are living on country, in culture, in language, so it’s then settling their arrangements (in terms of the projects and their impacts) with the Queensland Government, other proponents like Glencore or even within the community itself.”

Aurukun on Cape York is the homeland of the Wik people.

Aurukun on Cape York is the homeland of the Wik people.

Dominic calls the space he works in a ‘complex mosaic’ with competing needs and desires not just among the four groups involved, but often inside the various groups as well.

It takes understanding, patience, transparency and willingness to go on a journey, he says, but the work of generating outcomes that benefit all involved is deeply satisfying.

Dominic’s understanding of and respect for Indigenous communities and culture is one of the keys to his success. As one of eight children, he grew up in some of Australia's most remote regions. Born in Port Hedland, Western Australia, he later lived in Darwin and Townsville as his father, a meteorologist, moved the family across the country.

St Mary's Star of the Sea Cathedral in Darwin.

St Mary's Star of the Sea Cathedral in Darwin.

“He was actually the meteorologist on duty for Cyclone Tracey,” Dominic says. “We were little Catholic altar boys, so we had been to Midnight Mass at St Mary’s Cathedral that night and by the time we got home it was like, ‘Oh this is serious’.”

Growing up in more remote communities meant Dominic was exposed early on to a variety of different cultures, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, particularly the connection to country of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.

“I think it’s unfortunate that that more Australians don’t have a deeper understanding of the relationship that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People have to the land and waters that they live upon,” Dominc says.

“Importantly, if they did, I think that they would go ‘wow’. What never ceases to amaze me is that when tourists come to Australia they want to see, essentially, three things - the Sydney Opera House, the Great Barrier Reef and Uluru.

“What that tells me is they want to see natural beauty – they are saying ‘we want to see the particular culture you have here in Australia, Indigenous culture, as well as some of the great things you’ve done as a nation'.

“It’s unfortunate that more Australians don’t take the opportunity to understand it and don’t fall for the easy trap of thinking ‘oh, this is just being done to stitch us up’, or that it’s ‘inconvenient’.”

Contrary to popular belief, it’s rare that Indigenous communities and native title holders come at a project proposal from a starting position of ‘no’, Dominic says. They want to be treated with respect and made aware of the impacts and benefits of any project, so that they can make informed decisions about them.

But the vastly different approach to decision-making in Indigenous culture can require Dominic to untangle some interesting and sometimes amusing misunderstandings.

Dominic (right, centre) at a Board Meeting of Aak Puul Ngantam Limited, which represents the Southern Wik and Kugu People.

Dominic (right, centre) at a Board Meeting of Aak Puul Ngantam Limited, which represents the Southern Wik and Kugu People.

Used to the hierarchical nature of Chinese business culture, one project proponent struggled to cope with the collective decision-making processes favored by Indigenous groups.

“He was saying to me, ‘Hey, we’ve got an important decision we need, who is the boss? This person has been talking a lot today, does that mean he’s the boss today?’.

"I had to explain to him that there’s no bosses, the community makes the decision and these people are only here talking to us on behalf of the community, and then they will go back and talk to the community.

“In Indigenous communities, yes there are particular people with particular responsibilities but it's ordinarily about the community, not the individual.”

They also rely on advice that can confuse those from non-Indigenous cultures. With such a deep connection to the lands and waters on which they live, comes a connection to its wildlife.

In one community, they need to hear from the spirit of the palm cockatoo – a powerful totem in that culture – before the project can go ahead.

“I hear that and I just think that’s pretty impressive, it’s really quite amazing.”

For Dominic, that understanding of where everyone around the table is coming from is what gets the best outcomes in a negotiation.

He credits his Master of Laws at Bond University with refining his approach of interest-based negotiation, focusing on the impacts and benefits rather than bargaining from a fixed position.

“An open mind is a demonstration of a sophisticated client. Everyone knows it’s easy to articulate what you want. Interest-based negotiations look at what are the impacts, what are the benefits?” he says.

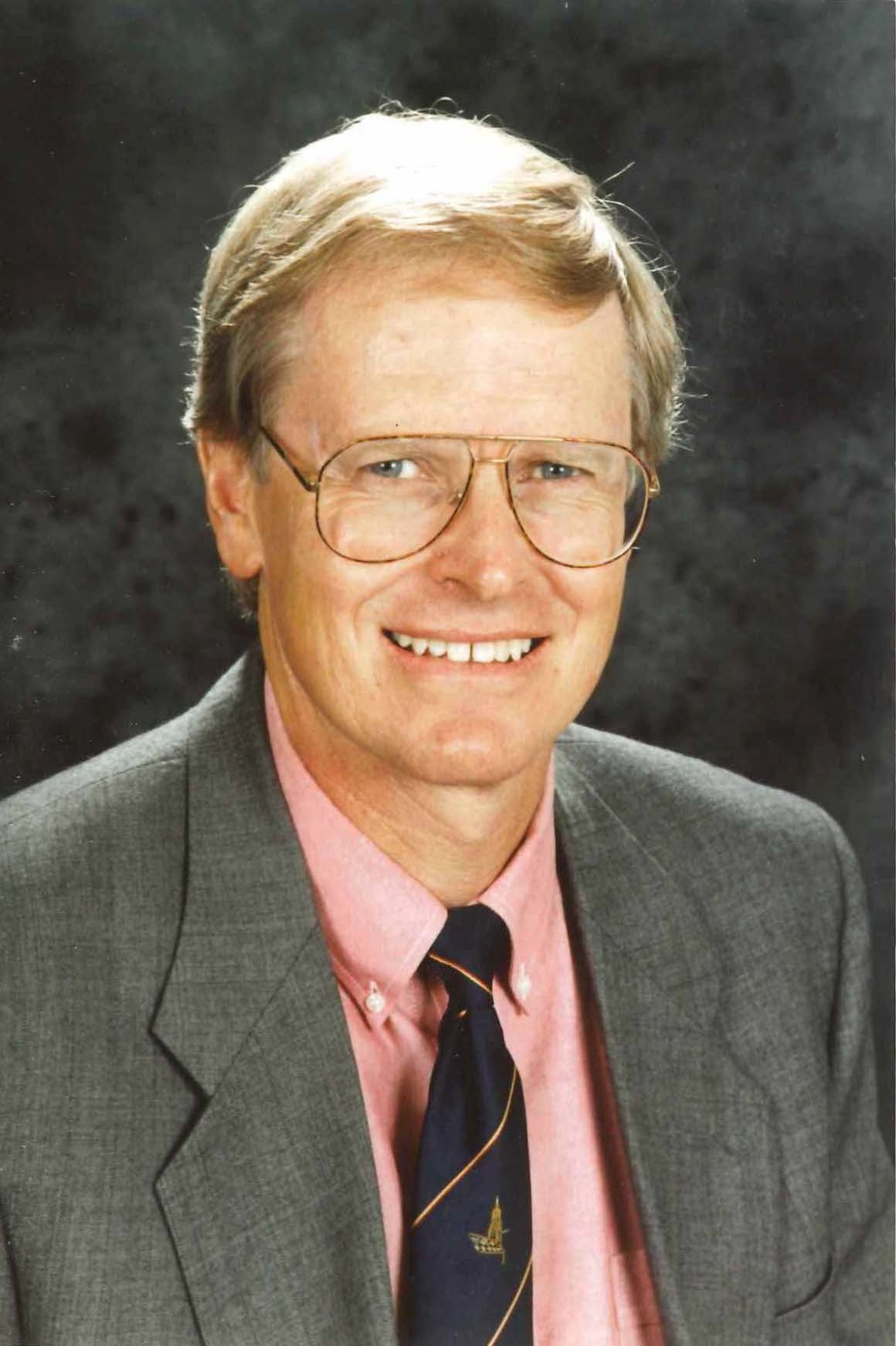

Professor John Wade in 1992.

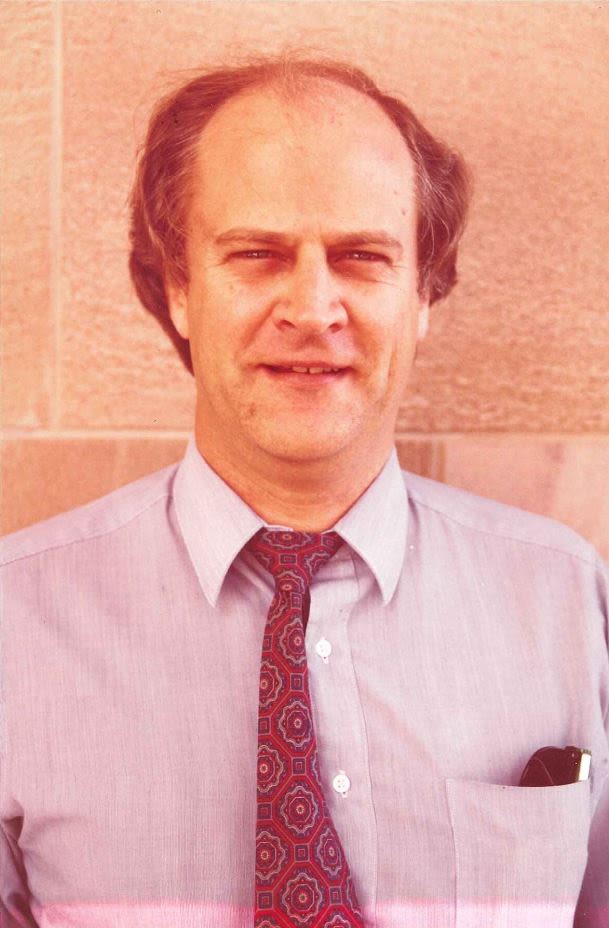

Professor Laurence Boulle in 1992.

Professor Laurence Boulle in 1992.

Professor Laurence Boulle in 1992.

“This is a classic example of something I found that Bond has always focused on. Two lecturers in particular – Professor John Wade and Professor Laurence Boulle - who I maintained a long respect and affection for.

“They were both wonderful illustrations of this style of negotiation, which is really what I think is important in these situations – you've got to concentrate on the issues, not the people.

“I really owe a debt of gratitude to John and Laurence, all those 30 plus years ago now. Their lessons certainly continue to ring true.”

Published on Wednesday, June 18, 2025.

Original thinking direct to your inbox

Stories from Bond