To Western ears, music from other cultures can sound jarring. Learning to appreciate it creates a more harmonious world.

From Mozart to Billie Eilish, music has the power to move listeners in deep and profound ways. Beethoven’s Ode to Joy is a soaring anthem of hope and elation.

Adele’s Someone Like You is a sorrowful ballad that can bring listeners to tears.

But that emotional connection doesn’t always translate across cultures.

I was recently involved in a study led by my PhD student Marjorie Li that looked into how Western listeners perceive emotions in two distinct musical styles: Western classical and Chinese traditional. To do this, music experts curated a series of 10-second sound clips — half Western classical violin music and half Chinese traditional music played on an erhu, a two-stringed bowed instrument. The erhu sounds like this:

Each sound clip was selected to reflect one of four emotions: happiness, sadness, agitation and calmness. Along with Dr Kirk Olsen, a colleague from Macquarie University, we recruited 100 listeners of white European descent and based in the UK, US, New Zealand and Australia.

Perhaps the most interesting finding from this research was that the listeners tended to perceive Chinese music as “agitated” and Western music as “happy”.

Why is this?

It’s a form of cultural bias.

We tend to associate foreign music with negative or disturbing emotions, and familiar music from our own culture as pleasant and reassuring.

These biases mirror broader misunderstandings between cultures — but history reminds us that music can do more than soothe; it can unite in powerful, even political ways.

In 1989 as the Berlin Wall crumbled, concerts near the wall became rallying points for East and West Berliners. David Bowie’s emotional performance of Heroes in 1987, just meters from the wall, is widely credited with inspiring hope and defiance in East Germans.

In a world of geopolitical conflicts headlined by the US-China trade war, could music play a role in bridging divides and fostering understanding?

An earlier study by the same research team suggests it can. We found that teaching people to play a musical instrument from an unfamiliar culture, even learning to play a single tune, can diminish or even eliminate biases about that culture. In that study, 58 white Australians were randomly assigned to learn either the Chinese pipa or a Middle Eastern oud (both instruments are similar to the lute).

A Chinese pipa.

A Middle Eastern oud.

After a two-hour lecture on the instruments’ cultural and musical background, the would-be musicians spent another couple of hours learning to play a folk song. Afterwards, they were more empathetic toward people of different cultural backgrounds. Pipa learners felt more connected to Chinese people, while oud learners felt more connected to Middle Eastern people.

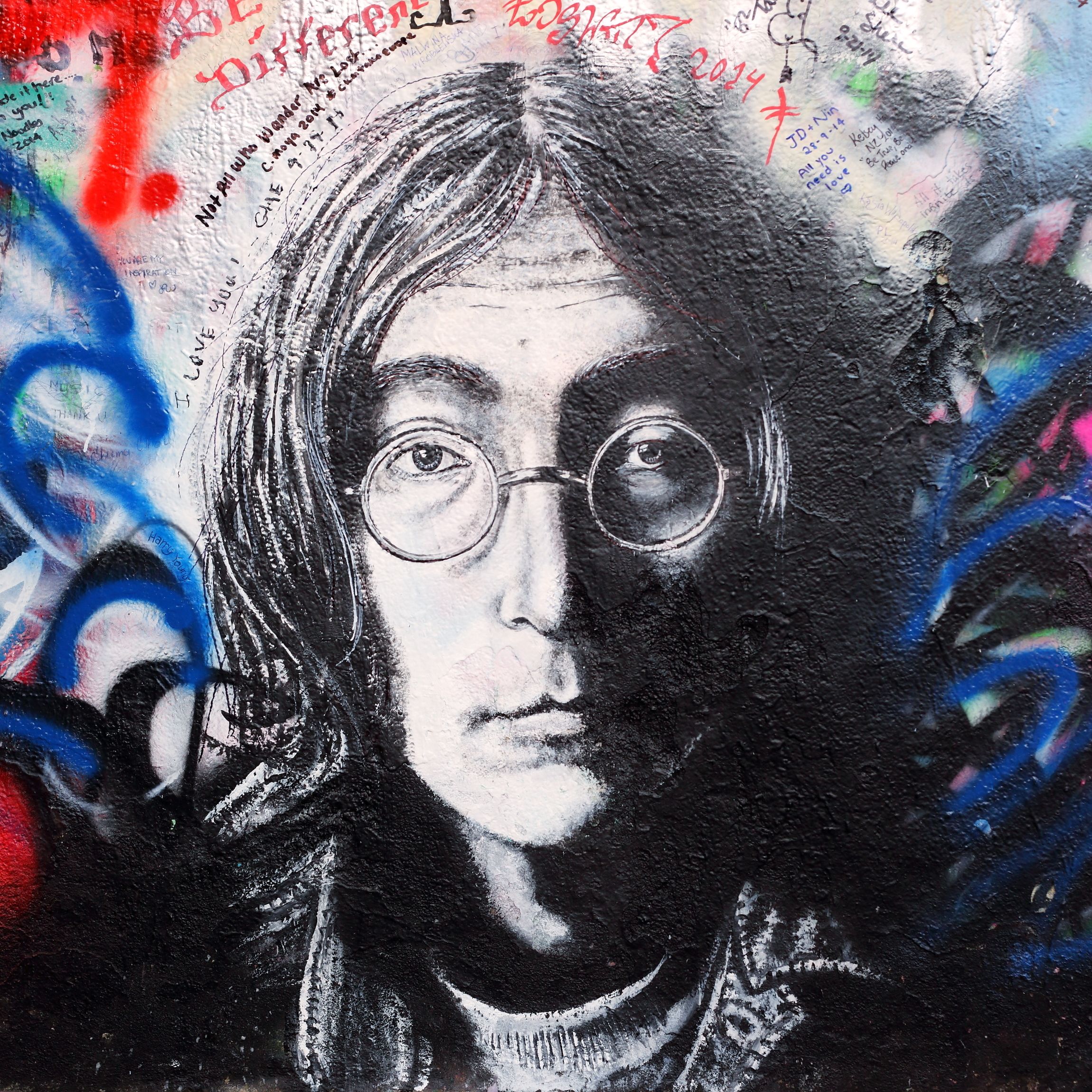

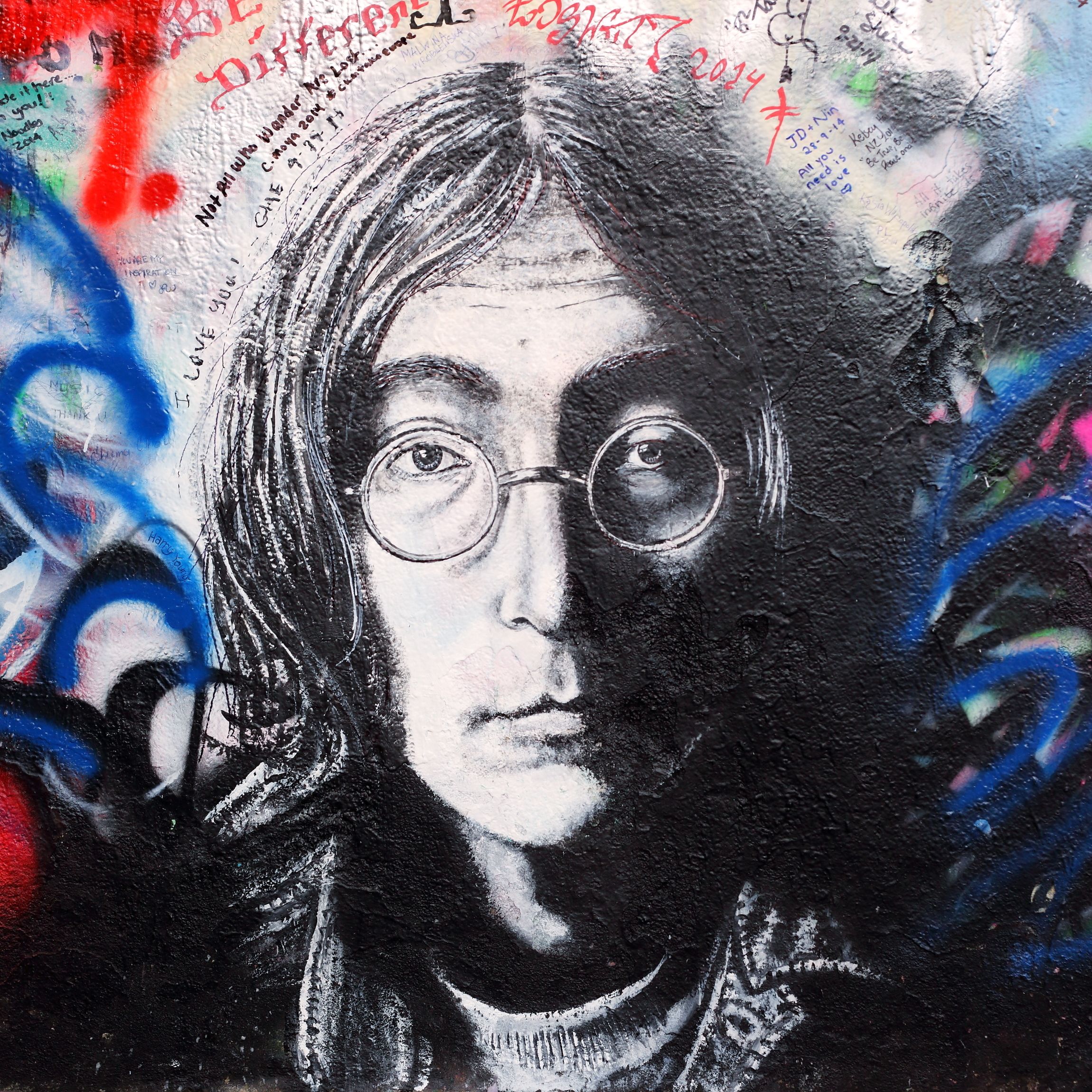

John Lennon understood this well.

His anthem Give Peace a Chance became a rallying cry of the anti–Vietnam War movement, uniting millions across borders under a shared call for peace. Music didn’t end the war, but it gave voice to a global conscience.

Asking Donald Trump’s trade negotiators to pick up a Chinese pipa to help find an amicable end to the ongoing tariffs dispute is a bridge too far. But there’s no doubt music can build unity if we’re all singing the same tune.

After a two-hour lecture on the instruments’ cultural and musical background, the would-be musicians spent another couple of hours learning to play a folk song. Afterwards, they were more empathetic toward people of different cultural backgrounds. Pipa learners felt more connected to Chinese people, while oud learners felt more connected to Middle Eastern people.

John Lennon understood this well.

About the author

Dr Bill Thompson is a Professor of Psychology at Bond University who specialises in the cognitive, emotional, social and cultural implications of music. Alongside members of the Music, Sound, and Performance Lab, he studies issues such as musical creativity, music and emotion, music and the imagination, musical disorders, and uses of music as treatment for neurological disorders such as dementia.

Published on Wednesday, 7 May, 2025.

His anthem Give Peace a Chance became a rallying cry of the anti–Vietnam War movement, uniting millions across borders under a shared call for peace. Music didn’t end the war, but it gave voice to a global conscience.

Asking Donald Trump’s trade negotiators to pick up a Chinese pipa to help find an amicable end to the ongoing tariffs dispute is a bridge too far. But there’s no doubt music can build unity if we’re all singing the same tune.

About the author

Dr Bill Thompson is a Professor of Psychology at Bond University who specialises in the cognitive, emotional, social and cultural implications of music. Alongside members of the Music, Sound, and Performance Lab, he studies issues such as musical creativity, music and emotion, music and the imagination, musical disorders, and uses of music as treatment for neurological disorders such as dementia.

Published on Wednesday, 7 May, 2025.

Original thinking direct to your inbox

Stories from Bond