When I was nine, I watched the 1984 Olympic Games. They were held in Los Angeles, and I don't know if it was the glitz and the glamour and the backdrop of Hollywood but watching it, I thought ‘that's what I want to do. I want to go to the Olympic Games.'

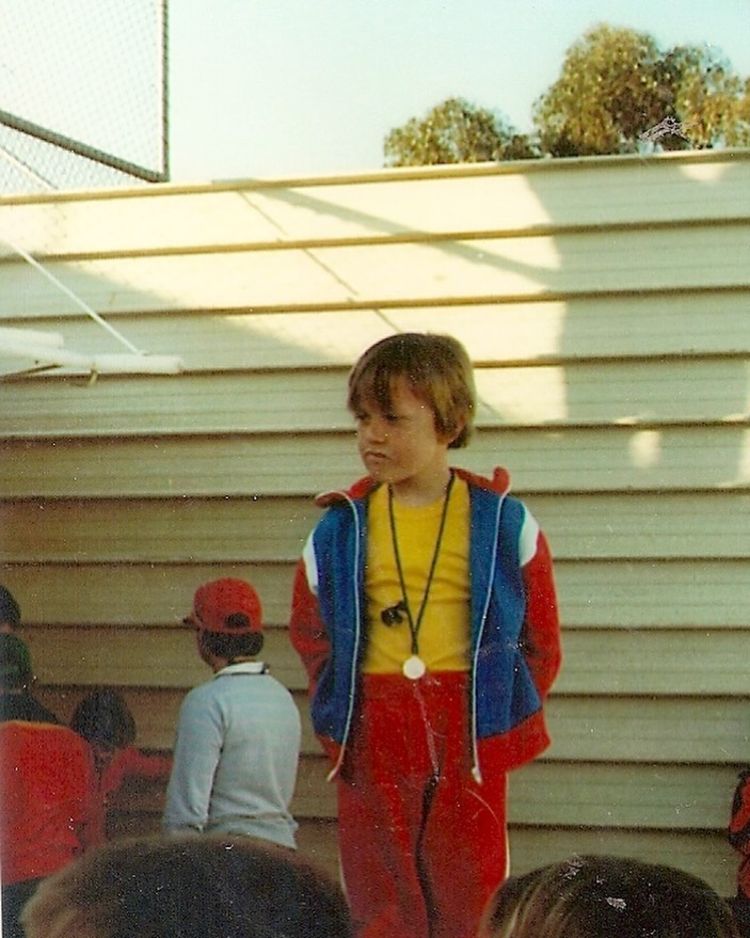

Back then I didn't fully understand what it took. My parents say that I asked them, "do we just go to Kmart, buy a tracksuit, and then buy a plane ticket? And when I get there, they give me a gold cap and I can swim?” My mum rolled her eyes and said, “yes, Daniel, that’s what you do. That’s how you get to the Olympic Games.”

I grew up in the Michael Jordan era; I wanted to play basketball. I loved tennis but I couldn’t serve the ball over the net into that tiny little square on the other side. I tried Aussie Rules but I couldn’t kick the ball and run at the same time. But I could swim, and I always loved swimming.

I was not a great swimmer. I was not earmarked for greatness. But between 4 April 1992 to 20 July 1996, my sole purpose in life was to swim and to go to the Olympics.

You may be wondering: what happened on 4 April 1992?

That night was the Olympic Trials. I was 16 years old and I was competing in the 1500m. Only first and second place were selected to go to the Olympics. I placed third.

After missing out on the Olympics, I spent the next four-year Olympic cycle training hard. I finished high school and I received a Vice Chancellor’s Elite Scholarship to study at Bond. I started my degree but didn’t finish it until nine years later. And in that time, I made a lot of silly and stupid decisions.

I can look back on my journey now and feel proud of what I’ve achieved and been through. But that wasn’t always the case.

Let me set the scene. It’s the 1996 Olympic swimming trials. Four years have passed since I missed out on selection and I’m determined to rewrite history.

I qualified in the 200m freestyle, 400m freestyle and 1500m freestyle. I beat Kieran Perkins – defending Olympic champion, world record holder and world record champion – in the 1500m. At the press conference after the race, no one asked me any questions. I think they were as shocked as I was. Kieran was the golden child of the Australian swim team. He was my hero.

My journey at the Olympics was a rollercoaster. I ran around with my wind-up camera, I had an autograph book I filled with signatures. I was starstruck.

My first event, on the 20th of July 1996, was the 200m freestyle. I didn’t expect much from the race. I just scraped into the final with a personal best time. When I hit the wall in the final, I turned around to the scoreboard and saw the number three next to my name. I’d won a bronze medal at the Olympics. It was the best feeling I’d ever felt in my whole career.

It wasn’t a gold. It wasn’t a world record. It was a bronze.

Fast forward six days and it was time for the 1500m freestyle. For as long as I could remember, that had been my race. My event. It was my perfect opportunity.

Kieran Perkins qualified for the final in lane eight as the slowest qualifier. I was in lane four, the fastest. But I knew from the moment that he qualified in lane eight, I wasn’t going to win.

I wasn’t mentally strong enough. I didn’t have the confidence or the self-belief.

My whole identity was being a swimmer, yet I stood up on the blocks and was petrified. I was scared of what would happen if I didn’t win. And I didn’t win.

When I saw the number two next to my name, I felt the worst I ever had in my career. I felt like I had failed; I felt like I’d let my friends and family down. My parents moved all the way from Adelaide to the Gold Coast for my swimming and I felt I needed to win that gold medal.

I was the first swimmer in 92 years to win a medal in the 200m, 400m and 1500m freestyle events at the same Olympics. But it wasn’t enough.

Daniel Kowalski (left) and Kieran Perkins on the podium at the Atlanta Olympics. Source: Supplied.

Daniel Kowalski (left) and Kieran Perkins on the podium at the Atlanta Olympics. Source: Supplied.

The following years were tough.

I went to the Sydney Olympics, and I won the gold medal I so badly wanted for swimming in the heat of the 4 x 200m freestyle relay. But I was empty and I was lost.

The one thing that helped me get back on track was going back to university.

I had to ask Bond if I could be reinstated after a lengthy period of absence. I’m so grateful that they let me do it.

Returning to campus as a mature-aged student, who didn’t know who I was and what I wanted to do, a retired swimmer at 27, was scary. But I went back into that environment and I immediately felt like I was part of something again.

My Bond experience helped shape me into who I am today. I was wrestling with a lot of personal fears and failures of where I was as an athlete, but the University helped me to become more of a whole person. They helped me to embrace disappointment, embrace what I felt was failure. They taught me to realise it’s okay to have regrets.

One of the most important things I learnt was the importance of networking and relationships. Here I was thinking I was alone in what I was feeling and going through, but I was surrounded by so many people who had shared experiences and wanted to get the same thing out of it.

The relationships I have with the peers I went to Bond with are very tight. We rode the rollercoaster together, the highs and lows of everything that life threw at us.

And more than anything, at Bond I realised that supporting others is what I wanted to do.

Today I’m the Head of Olympian Services of the Australian Olympic Committee. In my role I look after the career support, transitional support and mental health and wellbeing of Australia’s Olympians. I am able to help ensure they are provided with everything they need to be successful in life.

Being an Olympian is a small, exclusive club. Only 4,554 Australians have gone to the Olympic Games. I want to ensure that those Olympians don’t fall on the hard times that many have. To me, that’s really important. I learnt those values from the way I was treated at Bond.

At the Paris Olympics in 2024 I stayed in the Olympic Village for six weeks and was essentially a concierge for our Australian Olympic team, helping them with whatever they needed during the competition.

It’s the most incredible experience to be surrounded by young men and women, and the coaches and their support crew. Being part of their journey and life was really rewarding.

I often reflect back on my career and my time at Bond, along with everything that happened in those nine years.

Everything changed for me when I realised that the true measure of success wasn’t winning a gold, silver or bronze medal. It was how I acted, how I embraced experiences and appreciated the journey.

I thought I had to win for people to love me. At Bond I realised that wasn’t the case.

Now, I get to share those lessons and make an impact on the new generation of Olympians.

I think nine-year-old Daniel, dreaming of a Kmart tracksuit and a gold swimming cap, would be proud too.

Published Wednesday, 10 September, 2025.

Original thinking direct to your inbox

Stories from Bond