Handheld hazards

The scientists searching for sanitary solutions following viral mobile phone study

A Bond University study profiling the microbes on travellers’ mobile phones went viral, with news organisations across the globe reporting the surprising findings. Looking at 20 mobiles phones of foreign delegates attending the World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA) conference in Sydney, the study uncovered new insights into phone hygiene. We spoke to the researchers about the study, what it means for phone users, and how we can keep our devices safe.

A harbour for microorganisms

The study found an astonishing 882 bacteria, 1229 viruses, 88 fungi and 5 protozoa or parasites across just 20 mobile phones. “I was extremely surprised,” Senior Research Assistant Dr Matthew Olsen says.

“We can understand that mobile phones harbour almost every single microorganism that exists in some way, shape, or form but protozoa or parasites are particularly nasty and deadly. To find them on mobile phones is very interesting.”

The study also found 142 antibiotic-resistant genes and 224 virulence factor genes, which allow microorganisms to prevent key medications from affecting them enabling them to still be pathogenic to humans.

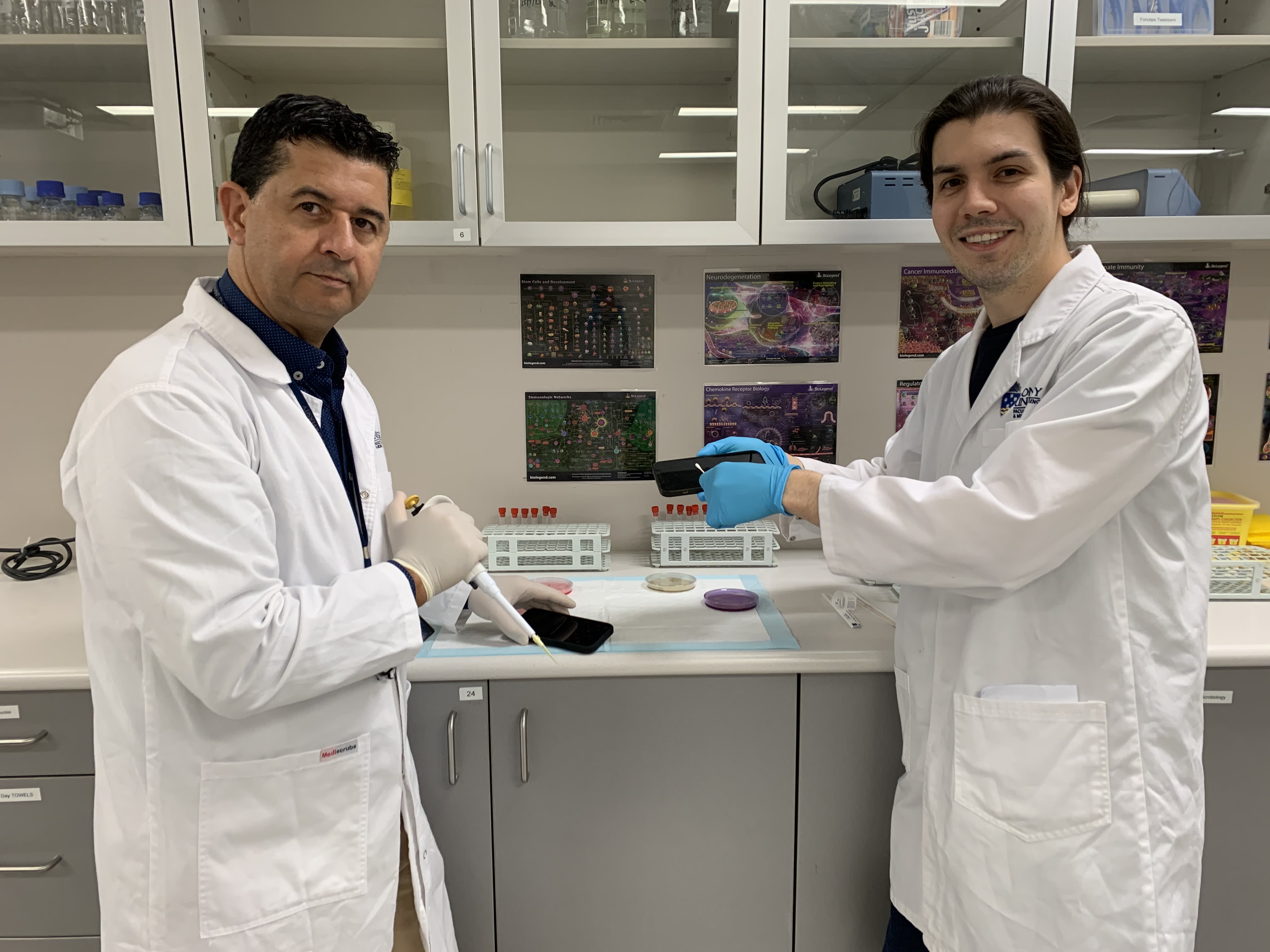

Dr Olsen carried out the study alongside several other researchers including mentor and Bond Associate Professor of Genomics and Molecular Biology Dr Lotti Tajouri.

The pair first came together to research mobile phones for Dr Olsen's honours, and again to examine the way contaminated mobile phones act as Trojan horses for the dissemination of microorganisms for his PhD. They originally worked with the Royal Australian College of GPs to assess how healthcare workers in Australian hospitals perceived their phones as a means of bypassing hand hygiene.

The team behind the WONCA study was structured around three chief investigators; Secretary General of the World Police Summit Dr Rashed Alghafri, Professor of Biosecurity at Murdoch University Dr Simon McKirdy, and Dr Tajouri. The research team saw the WONCA conference as an opportunity to gain a broader understanding of the perceptions of doctors from different countries.

“We sampled their phones and asked them questions to gauge their views on novel technologies to clean their phones and mitigate the risks associated with microbial contamination,” Dr Olsen says.

Dr Tajouri and Bond Univesity Professor of General Practice Dr Mark Morgan presented the findings back to the GPs on the final day of the conference.

"The presentation shocked a lot of the attendees when they were confronted with the types of microbes found on their mobile phones," Dr Tajouri says.

Spreading diseases

Infectious diseases are on the rise globally each year and Dr Olsen says scientists haven’t yet figured out solutions. “We saw during COVID it was quite hard to determine where exactly we got an infectious disease from,” he says. “We don't know exactly where these other sicknesses are coming from either.

“It’s possible these contaminated platforms we carry around could contribute to people getting sick more often. It’s something we really need to be investigating.”

Dr Olsen says the more research that is carried out on the implications of taking mobile phones everywhere, the more answers we will have around the rise in sickness. He says researchers already have a strong understanding of how diseases begin and what the required dose is for people to become sick.

“We want to understand how many bugs are on the phone, whether they are communicating with each other, if their resistance has changed, and if there’s anything the phone does differently to other surfaces,” he says. “We know phones heat up if used frequently, but there are so many other characteristics about a phone that enable the perfect breeding ground for microorganisms. The more we understand that, the more we will know about the phone’s role in transmission of diseases.”

Spreading diseases

Infectious diseases are on the rise globally each year and Dr Olsen says scientists haven’t yet figured out solutions. “We saw during COVID it was quite hard to determine where exactly we got an infectious disease from,” he says. “We don't know exactly where these other sicknesses are coming from either.

“It’s possible these contaminated platforms we carry around could contribute to people getting sick more often. It’s something we really need to be investigating.”

Dr Olsen says the more research that is carried out on the implications of taking mobile phones everywhere, the more answers we will have around the rise in sickness. He says researchers already have a strong understanding of how diseases begin and what the required dose is for people to become sick.

“We want to understand how many bugs are on the phone, whether they are communicating with each other, if their resistance has changed, and if there’s anything the phone does differently to other surfaces,” he says. “We know phones heat up if used frequently, but there’s so many other characteristics about a phone that enable the perfect breeding ground for microorganisms. The more we understand that, the more we will know about the phone’s role in transmission of diseases.”

Finding solutions

More research is also needed to arrive at a viable and effective solution for the general public to regularly sanitise their phones. Dr Olsen says alcohol wipes might not do enough to eradicate the microbes on their surface. The research team is investigating alternative methods including industrial-grade Ultraviolet C (UVC) technology, which works by projecting UVC radiation at a wavelength of 253.7 nanometres.

“At this wavelength, the radiation is absorbed by the microbes and destroys the DNA completely, which kills all the bugs” Dr Olsen says.

“We’ve already published a scientific article demonstrating this. We’ve been able to show how — with just a 10 second UVC sanitisation cycle within a safe, enclosed system — all bacteria on a contaminated mobile phone can be destroyed

“We’re aiming to do more research within high-risk settings like intensive care units and operating theatres to ensure when health professionals use a mobile phone around immunocompromised patients, they have the potential to sanitise their phones with a certified and efficient UVC phone sanitiser”

Dr Olsen and Dr Tajouri swabbing for microbes in the lab.

Dr Olsen and Dr Tajouri swabbing for microbes in the lab.

Dr Olsen believes certified UVC sanitisers will become more widely available in the coming years and says they should be prioritised where there are immunocompromised people or high risk of transmission, such as airports.

Through their scientific publications, the team is seeking to provide evidence to public health authorities like the World Health Organisation (WHO) to assist in tackling the problem of contaminated phones internationally.

“All of my research addresses Sustainable Development Goals set out by the United Nations and can really make a difference in this world. If the WHO could open a discussion, then I think we would see companies that look at UVC gain momentum with this technology and have a greater impact on society.

“We could see sanitisers in shopping centres, for example, and greater attention and sensitivity when using phones in healthcare, childcare and food-handling settings.”

Being mindful

The WONCA study garnered national and international media attention and Dr Olsen believes the findings resonated with audiences so much because most people are highly attached to their phones.

Currently, there aren’t many affordable options for people searching for certified UVC sanitisers they can use at home. Dr Olsen explains it’s likely any devices marketed at affordable prices to the public aren’t going to achieve the desired result.

“People are searching for answers, which is fantastic, but we need more guidance and regulation from watchdogs,” he says.

“Once the technology matures, it will become cheaper, more robust, and hopefully it will be cost effective to have certified devices in homes.”

For the time being, the researchers recommend people become more mindful of the environments in which they take their phones. He says people should be leaving phones behind when using the toilet, preparing food, visiting grandparents, or if working in a laboratory.

The researchers from Bond University have further trials planned around UVC and optimal rates of sanitisation.

Learning from the past

Dr Olsen says the idea of sanitising hands was popularised in modern times by Ignaz Semmelweis, known as ‘the father of hand hygiene’. During the 1800s, the Hungarian physician discovered infections were being carried from one ward to another in the hospital where he was working. He realised the healthcare providers were transmitting infectious diseases via their hands.

“He found if they could get their hands in chlorine before leaving each room, they could prevent the transmission,” says Dr Olsen.

“Our research is taking a similar approach — highlighting how mobile phones are heavily contaminated and trying to intervene before we see widespread transmission of infectious diseases by means of this Trojan horse.”

Dr Olsen stepped into Dr Semmelweis’ shoes when writing his PhD.

“On the last page I had an image of Semmelweis and explained if he was alive today, he would be telling us to sanitise our phones because, in a way, they’ve become a third hand,” says Dr Olsen.

Published on 11 December, 2024

Original thinking direct to your inbox

Stories from Bond